THE EYE AT 50 BLOG

THE EYE AT 50 BLOG

It was fifty years ago today… Posted by Adam Macqueen, 25th October 2011 | 0 Comments

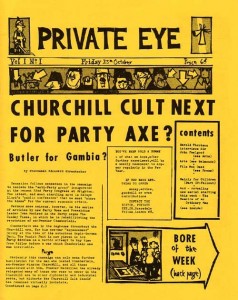

The very first edition of Private Eye, published on 25 October 1961.

Autumn, 1961. Beyond the Fringe is playing at the Fortune Theatre, earning such rave reviews that the prime minister himself has been tempted to come along and watch Peter Cook’s impression of him. Harold Macmillan’s smile is seen to falter slightly when his alter-ego veers off-script and proclaims that “when I’ve got a spare evening there’s nothing I like better than to wander over to a theatre and sit there listening to a group of sappy, urgent, vibrant young satirists, with a stupid great grin spread all over my silly old face.” Fresh from this triumph, the 24-year-old Cook is planning to open Britain’s first satirical nightclub, The Establishment, to ape the political cabarets of 1930s Berlin which, as he points out, “did so much to prevent the rise of Adolf Hitler.”

A year after the obscenity trial, everyone’s wife and servants have long since finished Lady Chatterley’s Lover and are now desperate to get their hands on Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. Kenneth Tynan has somehow managed to turn the job of theatre critic on the Observer into a position of national celebrity and cultural power. John F. Kennedy has taken over in America and failed to take over Cuba in the Bay of Pigs invasion not long afterwards. Britain has just sent George Blake to prison for 42 years for spying for the Russians, and let Jomo Kenyatta out. Adolf Eichmann is yet to find out the result of his trial in Jerusalem, but is probably beginning to suspect it won’t end well. Yuri Gagarin is back on solid ground and juke boxes across the land are pumping out the hot hot sounds of Petula Clarke, Del Shannon and Helen Shapiro. And in various pubs around London, various combinations of Shrewsbury and Oxbridge alumni are talking about setting up some sort of magazine.

“I remember discussions with Willie and me, and Wells was involved,” says Richard Ingrams. Willie was also party to discussions between Christopher Booker and his Liberal News colleague Bruce Page, though these seemed even less likely to come to fruition. “Page and I never really saw eye to eye on most things, it was never a serious proposition,” says Booker. “He became editor of the New Statesman eventually. It’s just a symptom of the fact we were all thrashing around. The key man was Peter Usborne. He knew that there was this loose chat, but he was determined to get on and do it. He was the man who said ‘an end to pub talk, let’s make it a proposition.’ He deserves a huge pat on the back.” Ingrams agrees: “Once Usborne got involved I thought it would happen. Usborne was a very dynamic character, and as soon as he got involved then it became possible. We needed a boxwallah to get things going.”

Usborne – who still resents Ingrams’ insistence on referring to him by the “colonial word for Indian chaps who slaved away at figures and didn’t actually run anything” – had spent most of the summer doing odd jobs in America, “and I kept on thinking about this suggestion that maybe we should do [our student magazine] Mesopotamia in real life. And when I got back I had a job as a trainee in an advertising agency, and I wasn’t terribly impressed with advertising as a way of life. I was starting effectively to do the research for setting up a new magazine in my lunch hours. I was going out to phone boxes and ringing up printers. I found a little printer and we discovered this new-ish technique called off-set litho which involved typing text on a typewriter and sticking it down and the printer would then photograph it, and that was it.” This was a pivotal moment in two ways. Off-set litho bypassed the need for expensive and unwieldy newspaper hot metal techniques and made a magazine financially possible. And the “little printers” were located in NW2. Their contract might only have lasted until issue four, when the plant’s owner Lord Rank found out about it and banned them, but without Huprint Private Eye would never have discovered Neasden. A mute inglorious Ron Knee there would rest, with Sid and Doris Bonkers guiltless of their country’s blood.

Someone – Usborne thinks it must have been Rushton – told him he should talk to “a very good writer called Chris Booker who was at Cambridge.” Booker had graduated from Cambridge to a job on official party paper Liberal News (he’d tried to get a job on the Evening Standard but failed to impress editor Charles Wintour when he fell asleep during his interview). He met up with Usborne, and quickly realised how seriously the young entrepreneur was taking things. “He sent me this very long memo, which I wish I still had, really setting out the business plan for how we were going to do it.”

It had a rather glaring hole in it. The minimum amount that Usborne reckoned they could get away with to set a magazine up was £300. And they didn’t have £300.

“I remember sitting in my flat in Kensington with Usborne and perhaps Willie, and we said ‘where the hell are we going to get three hundred quid?’” says Booker. “And Usborne said ‘I know! Andrew Osmond. His dad owns a supermarket chain in Lincolnshire and he’s got a bit of money.’”

“That was the day my life changed,” Osmond recalled. “I had gone to Paris to learn French before taking the Foreign Office exam. This telegraph arrived. It read, ‘Mespot. rides again. Come home. Uz.’” And so he immediately did. “By the time I got back and had found which pub they had moved to, they had completely forgotten about the telegram. Anyway, I had £450 and I agreed to back them with it. I became the original Lord Gnome.”

“It was enough to buy a car then,” Uz points out. “It was enough to start a magazine. And Andrew, Chris Booker, Willie Rushton and me were enough to get the thing going. And we did some of it in my flat in Islington and most of it in Willy Rushton’s mother’s flat in Scarsdale Villas in Kensington. And we concocted this magazine.”

This is part of the introduction from an early draft of Private Eye: The First 50 Years by Adam Macqueen. The version that made it into the book is much better. If you haven’t bought it yet, you really should – not least because Amazon have it at a special birthday price today.

More blog posts here »